Colville Reservation, WA

Joe Whittle

Images and words by Joe Whittle

Over the past six years, the Twelve Bands of the Confederated Tribes of the Colville Reservation (Chelan, Chief Joseph Band of Nez Perce, Colville, Entiat, Lakes, Methow, Moses-Columbia, Nespelem, Okanogan, Palus, San Poil and Wenatchi) have watched more than a half-million acres, about one-third of their 1.4 million-acre reservation, burn. Many homes have been lost and people displaced. Traditional use areas that Colville community members are dependent on for hunting, fishing, gathering and ceremony have been ravaged. The drier rain-shadow forests of the eastern side of the North Cascades region have not weathered the wildfire impacts of climate change as well as their wet western counterparts. Located right in the middle of those drying, drought-ridden forests, and holding some of the largest tracts of forest found on US reservation land, the Colville Reservation and surrounding national and state forest lands have been hit hard by repeated megafires.

Indigenous people are on the front lines of climate change around the world, and in the Pacific Northwest. These photos follow residents of the Confederated Tribes of the Colville Reservation and Northeast Cascades-Columbia Plateau region as they connect with the land and encounter challenges brought to their communities by climate change. Listening to voices from Indigenous communities can help us more deeply understand how we have reached this point of climate disaster, and how we might find our way out of it.

Lake Chelan-Sawtooth Wilderness Area. Kanim Moses-Conner and Polo Hernandez take a breather during an ascent to West Oval Lake on a drizzly Cascade day. Fireweed covers the forest floor, helping the ecology recover from the Crescent Mountain Fire, which burned over 50,000 acres during the summer of 2018.

Doug Marconi, Watershed Manager for the Confederated Tribes of the Colville Reservation, harvests medicinal “Labrador tea.” Much like the subalpine larch (Larix lyallii), Labrador tea (Rhododendron groenlandicum) is expected to suffer greatly from climate change due to its high elevation and habitat needs. The U.S. Forest Service has classified it as “extremely vulnerable.”

Relaxing and getting in a good laugh after a long day of hiking in the Lake Chelan-Sawtooth Wilderness Area.

“Places have memories. I've heard it said that a place is lonely for us. When we make a connection to that, when we begin to understand and be present and mindful, and unpack that, I think that beauty comes out. That light comes out. Then you begin to ask more questions because these things become illuminated inside you that you didn't even know you were really searching for and asking for.” - Doug Marconi

As fires have burned through traditional use areas, tribal members from the Colville Reservation have had to search farther and higher, and in fewer places, to gather the foods and medicines they need for subsistence and well-being.

During the summer of 2021, the Cedar Creek Fire burned over 50,000 acres. Fires raging throughout the summer closed the entire highway for a time, as well as many of the recreation sites, campgrounds, trailheads and wilderness areas in the region.

The Cedar Creek Fire burned right down to the North Cascades Scenic Highway and closed the Cedar Creek Trailhead and Trail, which leads into Lake Chelan-Sawtooth Wilderness not far from the famous Mazama Climbing Area.

The 2021 Whitmore Fire burned down to the shores of Omak Lake. Many ceremonial, historical, gathering and hunting sites have been impacted.

A fire line and burn scar from the Whitmore Fire.

Doug Marconi (Nez Perce/Palus) explains how the Whitmore Fire has impacted the Colville Reservation.

Darlene Wilder (Okanogan/Moses-Columbia/Palus/Nez Perce) walks a bulldozer track that was cut in directly behind her house to keep it from burning. Some of her neighbors just down the road lost their homes in the last round of fires.

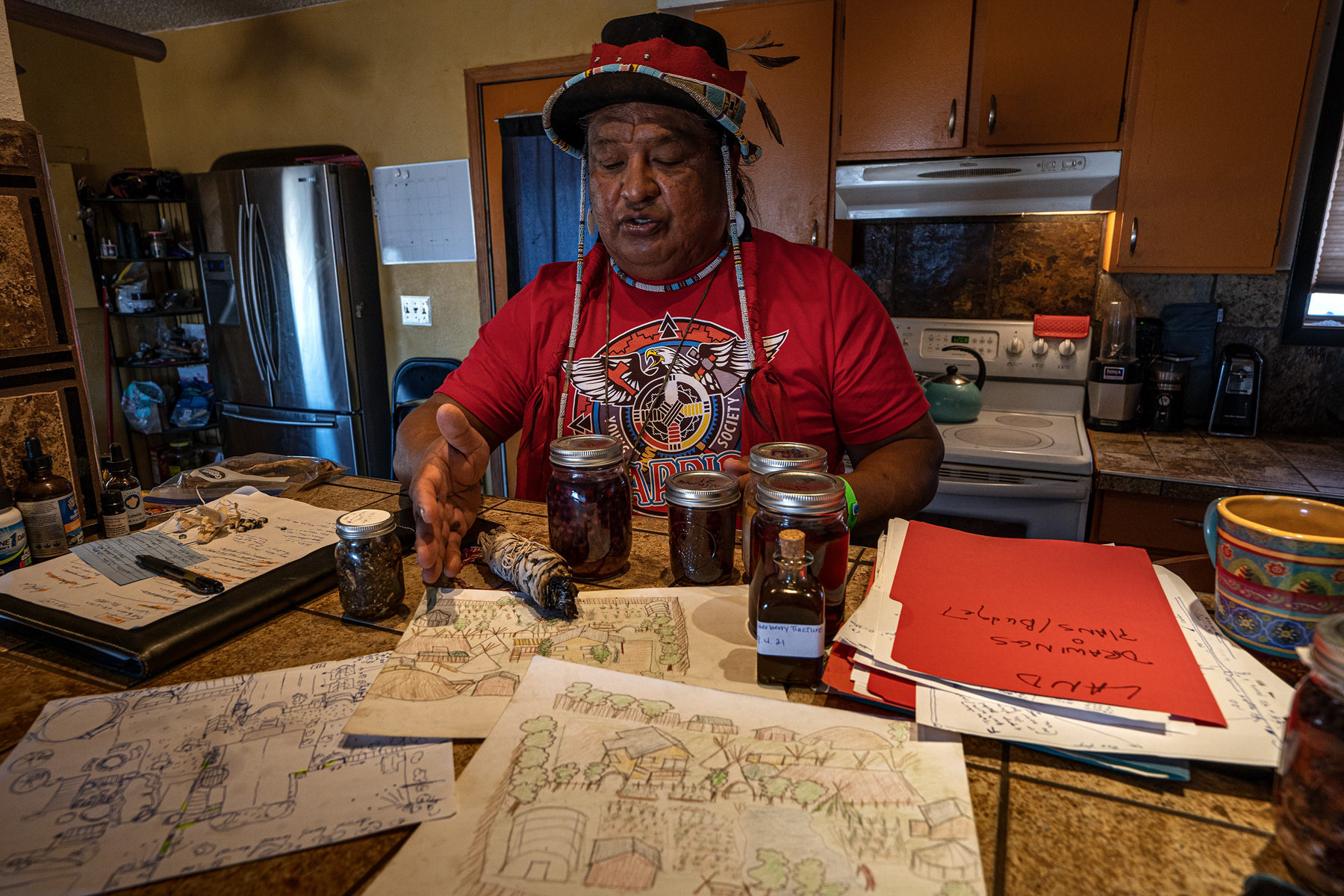

Dan Nanamkin (Lakes/Okanogan/Nez Perce) explains how he had to go up into the highest country of the Cascades to gather medicine roots. “That’s part of the challenge we are facing, is having to learn new territories on public land within our traditional homelands to gather in,” Dan explained.

Wearing a gathering basket woven by her great grandmother, who survived the infamous Nez Perce War of 1877 as a child, Darlene makes an offering to the land and roots to thank them for their gifts. Acres of charred, dusty bunchgrass prairie spread out behind her.

Former program director for the Environmental Trust Department of the Colville Confederated Tribes Amelia Marchand (Okanogan/Lakes/Moses-Columbia/Palus/Nez Perce) points at the Grand Coulee Dam, while describing how its construction disrupted not only the flow of salmon, but the entire ecology of the Upper Columbia River..

Dan founded an organization called The Young Warrior Society, whose mission is to make a space where Tribal youth are free to learn, to create and to cultivate deeper connections with their reservation and cultural practices. He leads workshops about food sovereignty at his home, demonstrating gathering as well as gardening practices that can be used to build climate resilience for his community. The hillside behind him is blackened and burned by the Chuweah Creek Fire that burned into the city limits of Nespelem.

Members of the Confederated Tribes of the Colville Reservation release Chinook salmon into the Columbia River above Grand Coulee Dam. Those gathered form a “bucket brigade” to pass each fish gently down the line from a tanker truck to the water.

The Colville Tribes began releasing salmon into the Columbia River above the Grand Coulee Dam in 2018. Before that, no fish had been able to move upstream from the dam for nearly 80 years. Members of the Confederated Tribes welcome the salmon back with ceremony, prayer, songs and speeches.

The Grand Coulee Dam. Dams are contributing to the impacts of climate change as well. Backflow that gathers behind them into reservoirs becomes stagnant and then begins to heat up, even in normal summer conditions, causing things like toxic algae blooms that have been lethal to people and animals.

People take turns releasing chinook salmon into the Columbia so that they can all have a hand in returning them to the river.

About Joe Whittle

Joe Whittle is a freelance photographer and writer living in unceded Nez Perce territory, in Joseph, OR. He is an enrolled Tribal member of the Caddo Nation of Oklahoma and a descendant of the Delaware Nation of Oklahoma. His photographs and writing can be found in publications including The Guardian, Alpinist Magazine, Outside Magazine, Backpacker Magazine, National Geographic Voices Blog and The Huffington Post. You can follow his work on Instagram @joewhittlephotography and at www.joewhittlephotography.com.

More stories from NativesOutdoors

Micheli Oliver

Truth, history and life in Blackfeet homelands

From one side of the Blackfeet Reservation to the other, the dynamic landscape is captivating, full of stories, lively people, culture and history.

Read more

Isaiah Branch Boyle

Restoring balance in the San Juan Mountains

The San Juans are rugged, spectacularly beautiful, rich, and marked by the many legacies of unscrupulous resource extraction.

Read moreFor joining the movement to save our lands.

We were unable to process your request. Please try again.

1801 Pennsylvania Ave. NW Suite 200

1801 Pennsylvania Ave. NW Suite 200 Washington, DC 20006 1-800-THE-WILD (1-800-843-9453) member@tws.org