Study shows roadless forests are key to protecting national parks, drinking water, more

The Tongass National Forest is a natural carbon sink

Nelson Guda

Ecologist Travis Belote shows the conservation value of roadless forests is huge

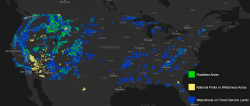

Most people who have spent time in a national forest have probably walked, hiked or camped in a designated “roadless area” whether they knew it or not. That is because roadless areas, named for their intact landscapes, are scattered across 39 states and encompass about 58 million acres of national forest lands. They are some of the closest publicly owned forests to many communities in the United States and were identified by the federal government during the past half century for their importance to wildlife, drinking water and general wildness.

Yet, until recently, little had been done to fully assess the conservation value of these lands. Scientists at The Wilderness Society and the U.S. Forest Service recently published the study Conservation Value of National Forest Roadless Areas showing just how important roadless forests are to climate change, drinking water, wildlife and landscape connectivity.

The research of Senior Ecologist Travis Belote and his team of scientists can also be seen in this roadless data visualization project that shows how roadless areas create a critical buffer zone between human development and permanently protected lands such as national parks and wilderness. One-third of roadless forests abut a national park or wilderness.

Destruction by logging is shown on the left in Targhee National Forest. This damage has impacts on Yellowstone National Park as welll. Had lands in Targhee been protected as roadless forest,Yellowstone would also be protected from the impacts of development.

Researchers also found that roadless areas contain important watersheds for drinking water and capture significant amounts of carbon, which helps dampen global warming.

"Protecting these places is a vital step toward ensuring a healthy, sustainable future," - Travis Belote, Lead Ecologist, The Wilderness Society

The science is clear: America’s forests protected by the Roadless Rule are some of the wildest, most important public lands in the country.

These scientific findings make today’s political reality even that much more concerning. Two decades ago, the U.S. Forest Service adopted a “Roadless Rule” to protect all remaining national roadless forests. Nevertheless, today many of these wild places are under serious threat of industrial development.

The Trump administration recently exempted the Tongass National Forest in Alaska from the Roadless Rule, flat out eradicating roadless protection on one of the most important national forests in the United States, if not the world. Protections have also been weakened in Idaho and Colorado, and the governor of Utah has requested flexibility for industrial development of roadless forests.

It’s time to fully protect roadless areas once and for all. Congress has that power.

Legislation such as the Roadless Area Conservation Act would permanently protect roadless forests and make it so that states can’t request special management permissions that would make roadless protections weaker. Congress needs to chart a more prosperous, secure future for our public forests and the people and wildlife who depend on them by passing the Roadless Area Conservation Act.

January marks the 20th Anniversary of the creation of the Roadless Rule. Following the passage of the Wilderness Act of 1964, the U.S. Forest Service inventoried America’s forests, identifying areas for possible wilderness because of their intact nature. The Roadless Rule protected these lands, banning road construction, logging and other industrial development. Since it was first implemented in 2001, the Roadless Rule has enjoyed overwhelming public support.

Yet, only 60 percent of those forests protected by the rule 20 years ago are still protected by it today. Millions of these forested acres have been siphoned off for use by corporate interests.

A few states have tried – some successfully such as Colorado and Idaho – to enact their own management of these forests. President Trump last month completely removed the Roadless Rule from Southeast Alaska’s Tongass National Forest, the largest intact temperate rainforest in the world. More than 9 million acres of pristine roadless areas in the Tongass – some with old-growth trees 800 hundred years old – are now open to logging and other industrial development.

The superlatives to describe the Tongass National Forest are endless: It supplies a quarter of all commercial salmon caught on the West Coast; it’s a globally-significant carbon reserve; it’s the largest national forest in the United States; its bald eagle population is larger than all others in the continental United States combined.

More importantly, the Tongass is the traditional homelands of the Tlingit, Haida and Tsimshian people whose lineage runs back deep in time. Many of the Alaska Native communities in Southeast Alaska rely on the Tongass and are fighting back to restore protections there.

If the crown jewel of the National Forest System is now open to industrial development, then all of America’s forests are in serious trouble.

The science is clear. The time is now. Permanently protecting our roadless forests would preserve drinking water, connectivity, our national parks and wilderness areas and would help all people, literally, breathe a little easier.