Public lands & the climate crisis: Drought

Shipwreck Cove, Lake Mead, Nevada, 2022.

James Marvin Phelps/Flickr

The Southwest has never been drier–let’s look to public lands

A 22-year-old in the U.S. Southwest has essentially lived their entire life in a megadrought. For over two decades, the region has faced severe and continuous dry conditions that are especially harsh in the summer. There hasn’t been a drought like this since the late 1500s, when the Ancestral Pueblos, Navajo and Apache were only just beginning to encounter Spanish explorers and colonizers in the area.

But as climate change worsens, this type of extreme weather is becoming more frequent—and severe.

While dry conditions are nothing new to the Southwest, researchers at Columbia University have found that climate change is behind this record-breaking drought. Changing rain and snow patterns combined with higher temperatures have increased the rate of water evaporation. Moisture is being held in the air while the lands below stay dry.

As global temperatures continue to rise, scientists expect other megadroughts on the horizon. Meanwhile, communities struggling with water shortages are eager to find ways to prevent them from happening again. A climate solution that has not been fully explored yet is public lands.

Clean energy, not fossil fuels

It’s hard to believe, but if public lands were their own country, they would rank fifth among the largest greenhouse gas emitters in the world. The reason: Decades of oil and gas drilling on these lands with very little scrutiny from the federal government, leading to an enormous amount of climate-changing pollution.

As we move forward, there’s a clear opportunity to change that reality. Instead of hosting fossil fuel extraction, these lands could be used to develop renewable energy in places that have low impacts on wildlands, wildlife and cultural resources.

Making the swift transition from a polluting, fossil-fuel economy to renewable energy would help slow down the climate crisis.

The Southwest is a great example of how impactful that shift would be. Fossil fuel development on public lands in New Mexico, Colorado, Utah and Nevada led to 210 million metric tons of greenhouse gas emissions (CO2e) annually. That’s as much climate pollution as would come out of the tailpipes of 45 million cars roaming the streets for a year.

Meanwhile, the region’s public lands have some of our nation’s best solar, wind and geothermal resources. The Bureau of Land Management (BLM) has identified 700,000 acres in the West where solar energy can be developed responsibly on public lands, avoiding sensitive wildlife habitats, migration corridors and cultural sites. A similar approach is already taking place in Nevada, with solar farms being installed on lands belonging to the Moapa Band of Paiute Indians.

Making the swift transition from a polluting, fossil-fuel economy to renewable energy would help slow down the climate crisis and potentially prevent future megadroughts. The Biden administration should embrace this plan – starting with public lands – while working with fossil fuel-reliant communities to ensure just economic transitions.

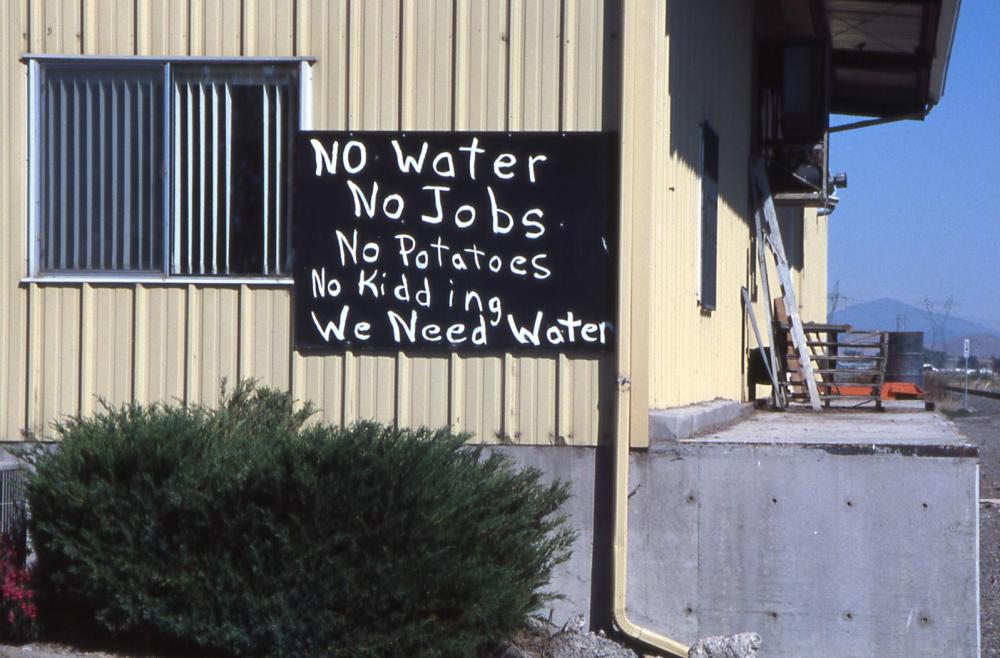

We need water

ODA/Flickr

Not addressing climate change with everything that we have—including public lands— will only lead to more droughts and dwindling reservoirs, rivers and lakes when we and wildlife need water the most.

This year, Lake Mead and Lake Powell—part of the Colorado River basin—are at record low levels, down to about 30 percent capacity. They are so low that a ring can be seen where the water used to reach, underwater vegetation is now exposed and decades-old murder victims are even being uncovered.

Large reservoirs like these provide drinking water for millions of people. When they go dry, rural communities are hit hardest; while larger cities can access underground reserves and supplies from other locations, more isolated towns rely on a limited number of wells that can easily malfunction.

Native communities and tribes are among the most vulnerable to water crises.

Native communities and tribes are among the most vulnerable to water crises. The federal government has often neglected to provide running water and drought solutions to tribal nations and other Indigenous communities. As climate change and drought worsen, tribes across the Southwest – and beyond – remain steadfast in demanding the U.S. government fulfill its commitments to their communities.

With the human impacts of severe drought and other extreme weather disasters in mind, the federal government must look at how it manages public lands – to be part of the climate solution instead of part of the problem.