We zoomed in to find creative climate and environmental solutions

Protesters march in Washington DC during the Global Climate Strike in 2019

Carla Ruas, TWS

Amid COP28 talks, creative strategies to resist and adapt to climate change

When the COP (Conference of the Parties) international climate change conference rolls around each year, and global leaders gather for two weeks to discuss how to combat the climate crisis, it’s easy to feel disheartened at the lack of progress being made on the international scale.

But this doesn’t mean no progress is being made. In fact, there are all kinds of solutions happening locally, particularly in places where people don’t have the time or choice to sit back and discuss how they plan to deal with climate change.

Whether it’s fighting for the right to clean air in southeast Houston, demanding a stop to the Mountain Valley Pipeline in Appalachia, expanding access to green spaces and food equity in Los Angeles or pushing for a clean energy transition amid New Mexico’s oil and gas boom—right now, all around the country, community leaders and advocates are implementing solutions to today’s environmental crises. And we have the stories to prove it.

What it’s like to live in an oil and gas boom

Extending across southeastern New Mexico and West Texas, the Permian Basin produces nearly 40 percent of all U.S. oil and gas and has more than quadrupled its output in the last decade. This oil and gas boom shows no signs of slowing down and will continue to have a massive impact on the climate, the environment and the people who call the Permian Basin home. We spoke with 10 community members who live in towns and cities across the western part of the basin, which is predominantly made up of public lands. Read their stories.

People living next to an oil and gas boom

Five stories of resistance in the era of fossil fuels and climate change

The fossil fuel lifecycle impacts our daily lives—from rampant oil and gas drilling, leaking refineries and destructive pipelines, to the climate pollution and extreme weather fossil fuel emissions create.

Right now, communities directly affected by this lifecycle are organizing, rallying and fighting back to undo our unstable and unhealthy reliance on fossil fuel energy. Their work is sorely needed. Read inspiring stories from activists, community leaders, lawyers, scientists, teenagers and mothers, spanning from Los Angeles to the Appalachian Mountains, on what it’s like to live up close to oil and gas infrastructure, and what it means to fight back.

Five people smile below text that reads "5 stories"

TWS

An oasis in the sprawl: expanding the San Gabriel Mountains National Monument

Los Angeles County is home to the San Gabriel Mountains National Monument, a treasured landscape of rare chaparral shrubland as well as oak and conifer forest. These mountains account for a whopping 70 percent of the county’s open space, welcoming millions of visitors every year for outdoor recreation and providing critical wildlife habitat in an otherwise dense urban area.

Elected officials, community leaders and local advocates are now calling on President Biden to expand the San Gabriel Mountains National Monument to include 109,000 acres of the adjacent Angeles National Forest. Hear from local voices on the many benefits of an expansion.

Clouds and grass surround the San Gabriel Mountains

Bob Wick

Growing greener, healthier cities, one garden at a time

Urban gardens are on the rise. In addition to letting people grow the fresh fruits and vegetables they need to live, urban gardens have proved vital in increasing some communities’ access to nature. Built into cityscapes in places like local parks and schools, urban gardens offer immeasurable benefits to people who might otherwise be without nearby green spaces. This includes better health, stronger community connections and an environment more resilient to climate impacts. Read stories about community members finding creative ways to create better access to nature through urban gardens.

Fremont Wellness Center and Community Garden in Los Angeles

Ahad Shahid

Voices of the east

The eastern United States spans 2,500 miles from Florida to Maine and houses the ancient Appalachian Mountain range, rich in biodiversity and a hub for movement, adaptation and resilience. It’s also home to some of the most beloved public lands in the nation. In a storytelling anthology, we featured five personal audio stories from individuals who call the East ‘home,’ exploring their ties to land, history, identity and more.

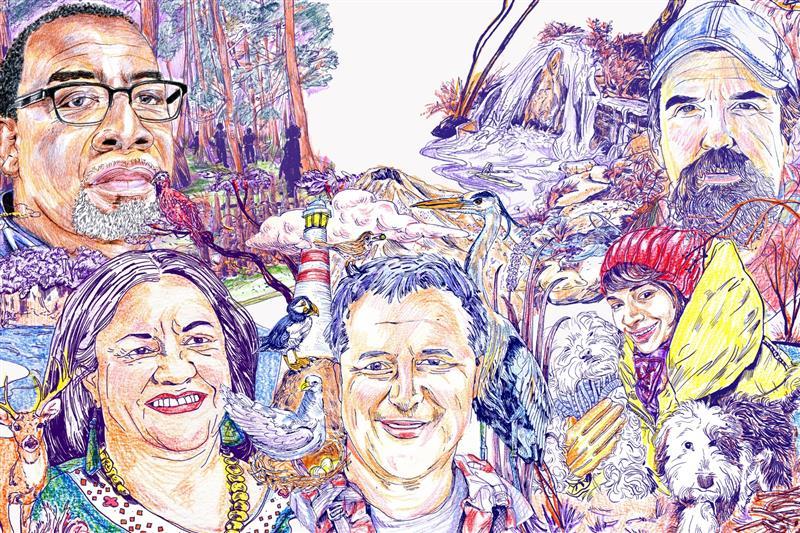

Drawings of five people interspersed with nature

From a former mining town to a revitalized community: Voices from Ajo, Arizona

The lands to the east of Cabeza Prieta National Wildlife Refuge in southern Arizona are colloquially known as “the Ajo block,” as they surround the former mining town of Ajo. In the 1900s, a massive open-pit copper mine—which stretched over a mile and a half across and 1,000 feet deep—provided thousands of jobs that kept Ajo booming. Since the mine closed in 1985, Ajo has evolved to become a diverse arts hub that attracts visitors—including RV nomads—from far and wide.

Currently, there's a community-driven proposal to expand Cabeza Prieta which would continue to support Ajo’s small community by boosting ecotourism, protecting critical wildlife habitat, and ensuring Ajo's "big backyard" of public lands is protected for cultural, ecological and natural values. This expansion would also protect land that is sacred to the Tohono O’odham and Hia-Ceḍ Oʼodham peoples who have called the region home since time immemorial. Hear from Ajo's community members on what this refuge expansion means to them.

Cuerda De Lena in the proposed expansion area of Cabeza Prieta National Wildlife Refuge, Arizona

Mason Cummings

Who is outdoorsy?

The future of public lands, and our fight against climate change, depends on building more inclusive outdoor spaces and an entire conservation movement. We need to dismantle the stereotypes that only a certain type of person—white, upper-class, thin, athletic and non-disabled – can enjoy public lands. In the series “Who is outdoorsy?" we explore how different communities connect with the outdoors and highlight the importance of working to make the outdoors more diverse, accessible and inclusive.

A collage of nine images of people outdoors

TWS

A new model for Indigenous-led conservation

As we come to grips with our past, the conservation movement is undergoing a transformation as well. Part of that is recognizing the pain behind the United States’ system of public lands—the enduring homelands of Indigenous peoples, taken from them without knowledge or permission. We must promote healing from the trauma associated with that legacy of assimilation and termination policies.

Using that reckoning as a starting point, the Imago Initiative is an innovative process of creating a new model for Indigenous-led conservation that recognizes and advances the rights of Indigenous peoples and uplifts their inherent, inalienable rights as the occupants and stewards of the land since time immemorial. Learn more about what it means to reimagine conservation through an Indigenous lens in the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge.

Mason Cummings, TWS

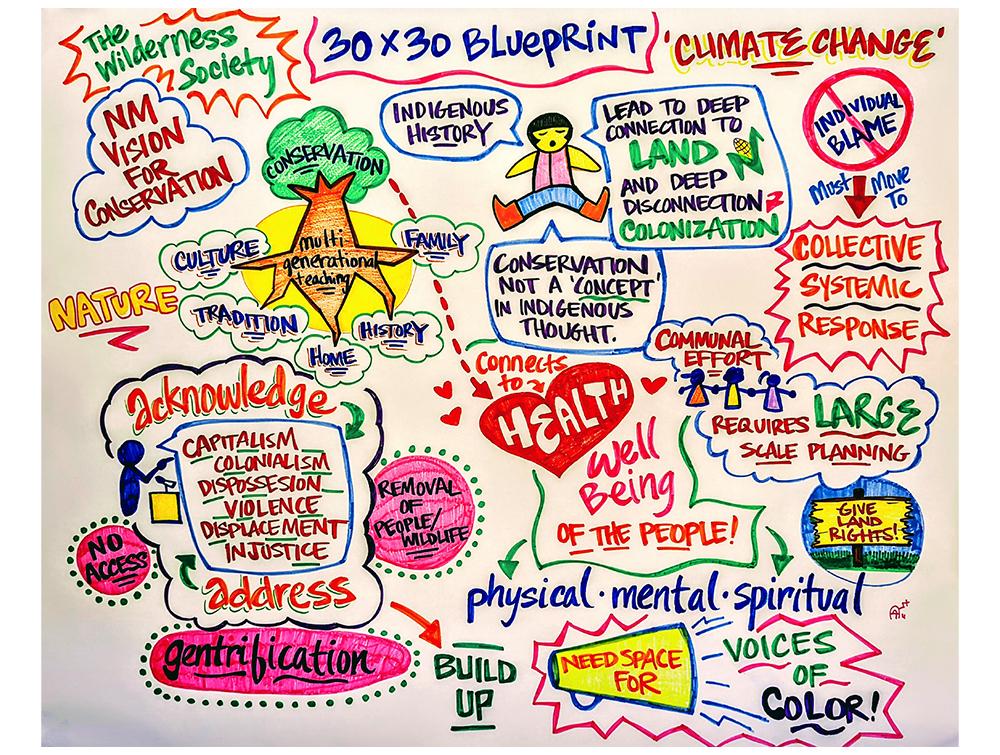

An inclusive, authentic New Mexico vision for conservation

While we need action right now to address the climate and extinction crises, the way we arrive at that action must be deliberate and inclusive. To better understand how communities across New Mexico currently view conservation, dozens of New Mexico leaders who identified as Black, Indigenous and/or people of color (BIPOC), or who worked at organizations serving these communities, shared how their lived experiences influenced their conservation practice.

A Climate Plan for Public Lands

To tackle climate change and support local communities, we need the Biden administration to take whatever strong actions are possible right now—and that must include creating and following a comprehensive climate plan for our public lands and waters. At The Wilderness Society, we have a five-point plan that we hope President Biden will adopt today!