How a new BIPOC-led conservation vision came to life

Images from Kay Bounkeua

How inequity, environmental threats and violence intersect—and how we move forward.

The story of how I ended up working to fight climate change and the extinction crisis starts with my parents’ story, when they experienced the U.S. military dropping more than 2.5 million tons of ordnance on Laos between the years 1964-1973—about a plane-load of bombs every eight minutes, 24 hours a day, for nine years.

That onslaught is what drove my family to the United States. Growing up, I recall hearing stories of them and their siblings hiding in caves, watching machine guns turned on their schools and homes and living in refugee camps. They eventually settled in Albuquerque, New Mexico—where I was later born—but these stories, and the lasting impacts of these experiences, have been an ever-present companion in my life.

Time outdoors helped me feel like I belonged and sparked interest in conservation

Kay Bounkeua

Growing up in a mixed-status family—or those with different citizenship statuses—who spoke English as a fourth language, being outdoors was one of the few times I felt belonging. Outside, amid the Sandia Mountains that seemed to connect us to the mountainous landscapes—like Phu Khao Khuay, by Vientiane—in Laos more than an ocean away, we could speak a mixture of Lao, Thai, Mandarin and English; eat traditional foods without critique; and not worry about how we dressed. Enjoying and valuing nature led me to an interest in the ongoing climate and extinction crises—and a closer examination of how these problems intersect with forced migration, violence and experiences like my family’s.

Visits back to Laos showed the beauty, richness and love of the people and the landscapes, but also reinforced how environmental, geopolitical, and economic turmoil interact and compound each other. I saw whole villages swallowed up by dams; entire sections of forests replaced by rubber trees, guarded by private security teams and tended to support a foreign economy; Indigenous communities exploited by tourism and farming disrupted by loss of land, resulting in a new generation of families forced to migrate from their ancestral lands to survive.

I’m still haunted by a story my dad tells—and spurred to continue my work. A farmer took an ax to an ancient tree next to his home. My father asked why he would do such a thing. The farmer, in tears, said the only option he had left was to sell the wood to feed his family for the week. Put simply, we can’t base our conservation strategy on the felled tree without also considering the empty bellies and futures of the farmer and his kids.

Mainstream conservation still excludes many—including communities most impacted by environmental threats

Kay Bounkea

As I learned more about how climate change, environmental destruction and violence fueled migration, I wondered who was leading conservation initiatives in New Mexico, and how such work was being carried out across different communities.

Specifically, I wanted to know who was making the connections between what communities were living through and the conservation policies ostensibly being proposed to help those communities. I began to attend conservation meetings and couldn’t help but notice that despite being in a state where people of color make up the majority, most of the others I saw were white. It seemed like I was one of the few people of color in conservation.

I couldn’t help but notice that despite being in a state where people of color make up the majority, most of those I saw in conservation meetings were white.

We all depend on the Earth’s air, land and water to sustain our health and livelihoods. But the stark lack of diversity at these meetings suggested that the conversations about how to steward and protect nature is excluding those who most need to be engaged. Climate change, pollution and loss of biodiversity most severely impact communities of color, yet youth and Black, Indigenous and people of color (BIPOC) are still an afterthought in conservation work. It’s irresponsible—and impossible—to make a legitimate plan to address these problems without leadership from these communities.

Taking the time to craft a BIPOC-centered conservation vision

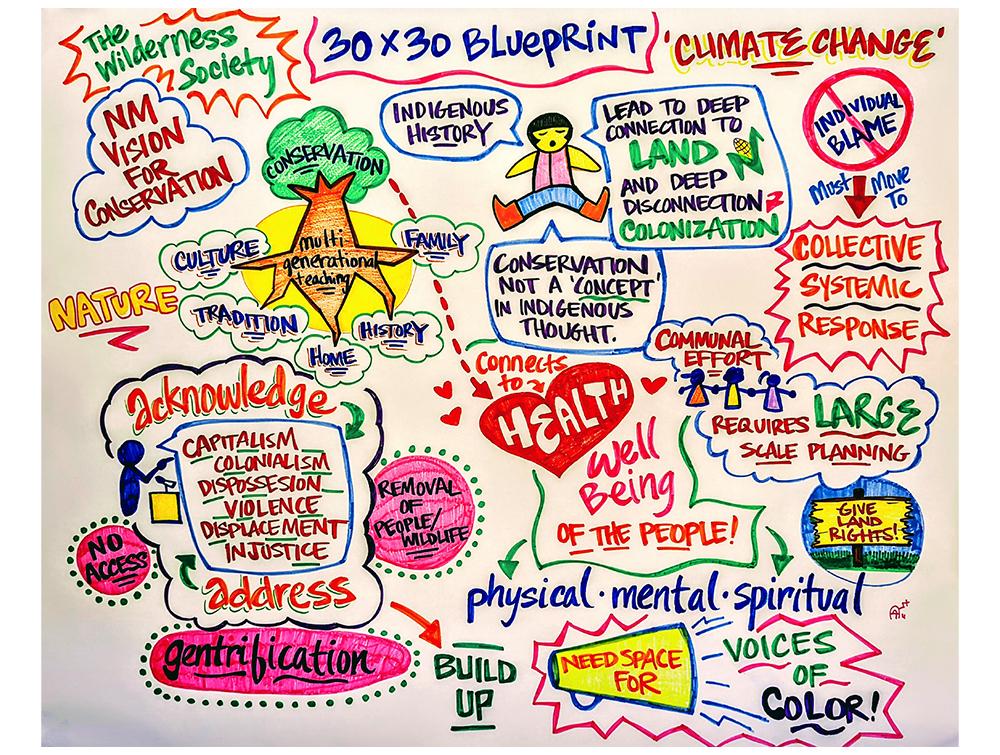

As a plan to conserve 30 percent of lands and waters in the state—paralleling national and international conservation goals—was being designed, I felt the tension between the urgency of this work and the need to move deliberately, taking care the right people are included. We do need to move quickly, but what’s the point if the foundation of the work is incomplete at best and broken at worst?

That concern led Wilderness Society staff in New Mexico to partner with Ancestral Lands Conservation Corp, Center for Civic Policy and NACA Inspired Schools Network. Together, we committed to over two years of listening sessions with BIPOC communities and youth and supported the leadership of over 150 individuals—the majority identifying as Indigenous and immigrant youth—to learn how conservation and their lived experiences were intertwined.

What blossomed out of these in-depth sharing sessions was a living BIPOC-centered vision of conservation for New Mexico. This vision recognizes that conservation is embedded in traditional lifeways as a collective, multigenerational practice that respects the connections between people and nature and protects the intrinsic value of Mother Earth.

The vision is also guided by those most disproportionately impacted by the adverse health impacts of being displaced and disconnected from one’s homeland. Finally, it acknowledges that conservation cannot be done without addressing the dispossession, violence and injustices that have happened and still happen under oppressive systems like colonialism and the heedless pursuit of wealth and profit.

And we’ve already started putting this vision to work. Together, we crafted a resolution for Bernalillo County committing to protecting 30 percent of lands and waters by 2030 (sometimes called “30x30”) that is directly informed by these communities’ experiences and values. When that resolution was introduced, we had youth and parents of color, climate and environmental justice leaders and conservation partners testify in support of the resolution. It passed unanimously, with enthusiastic bipartisan support.

Continuing to move urgently, but keeping relationships at the forefront

As we move forward, it’s with both urgency and an understanding that this work must include the people most directly impacted by the legacies of environmental racism. Young people and BIPOC people have the most to gain if we succeed in implementing a holistic and equitable conservation vision—and the most to lose if we fail.

We move forward with the hope of modeling a Justice40 framework within our state’s 30x30 rollout – where at least 40 percent of state resources allocated towards 30x30 are being invested in communities that have been overburdened by pollution and toxic environments.

And beyond any specific policies, we move forward in a process that respects engagement and leadership of BIPOC communities and youth. We do so with the hopes of getting closer to realizing a more grounded and whole conservation space that respects us as people and the ways we nurture and invest in a healthy relationship with the Earth.

As we find new ways to disrupt conservation practices that are exclusionary, we must find the interconnections that allow us to address the violence perpetrated against the Earth, as well as the violence that plays out within and against our communities.