Before Central Park came Seneca Village, Black community hidden in the heart of Manhattan

Central Park, New York City

EAMMON ASHTON-ATKINSON, FLICKR

Park’s establishment displaced thriving Black settlement

Author: Gracie Heim

Maybe you’ve already heard about this chapter in American history: In the early 1800s, New York City was filling up and expanding rapidly. People were desperate for ways to escape the city’s chaos. That urgent need for peaceful green space led to the creation of Central Park, which would become a national treasure and model for weaving nature into the big city.

But that version of the story leaves out a lot of important information. For one thing, this area in the heart of Manhattan was and is the ancestral homelands of the Lenape people. For another, Central Park’s development was only possible because of the forced displacement of Seneca Village, Manhattan’s first significant settlement of Black property owners.

Central Park is rightly celebrated and enjoyed nowadays, but as we continue working to make the outdoors more representative and equitable, it’s important we lift up these kinds of forgotten stories--tales of communities uprooted in the name of progress that continue to echo to the present day.

Central Park (and Manhattan) is Lenape homeland

The namesake of the island of Manhattan is the Lenape word Manahatta, meaning “hilly island.” It was home to the Indigenous tribe prior to any contact with European settlers. The Lenape relied heavily on their surrounding natural resources to aid them in their daily lives and even established trading routes along the Hudson River with other Indigenous tribes, including the Haudenosaunee, the Mohicans, and the Shinnecock.

After the Dutch arrived in the early 17th century, the Lenape helped the settlers adapt to their new environment and traded beaver furs for guns, beads and wool. However, in 1626, the Dutch “purchased” Manahatta island from the Lenape people--a one-sided transaction that was based on a huge gulf between the two cultures’ understanding of “property.” While the Lenape saw this as a chance to share, the Dutch soon began building a wall around their newly purchased land, marking the beginning of the Lenape’s forced removal from their homelands.

Hundreds thrived in vibrant multiracial Seneca Village

Fast-forward to the 19th century (and that familiar story above, about an overcrowded city and people seeking relief). You might know that Frederick Law Olmsted and Calvert Vaux developed the winning plan for Central Park's design, but you probably don’t know what preceded it.

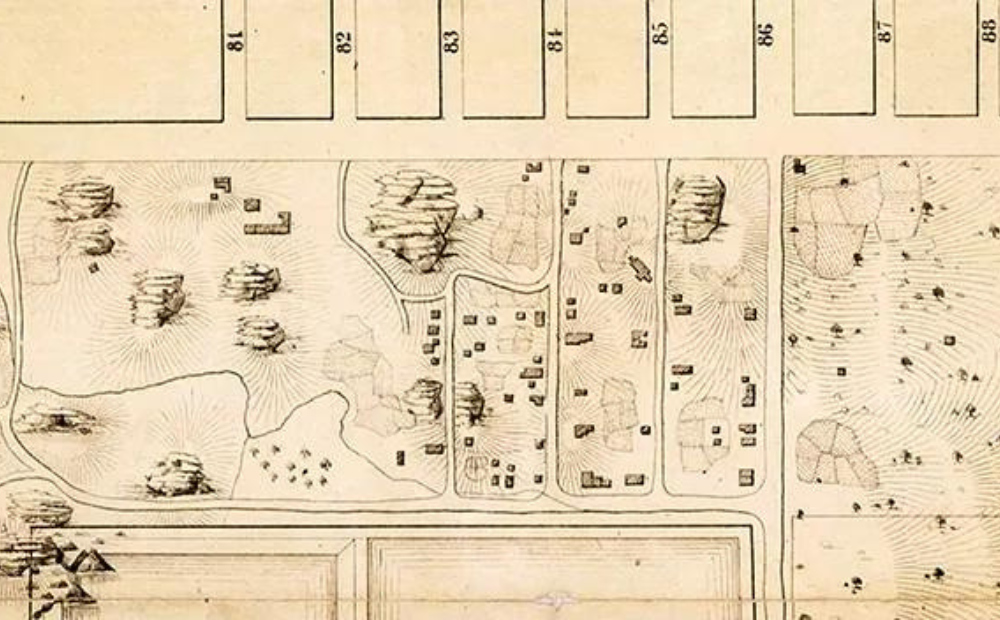

Before Central Park's creation, there existed Seneca Village, a vibrant community of free Black property owners in pre-Civil War New York. The community began in 1825, when landowners in the area, John and Elizabeth Whitehead, subdivided their land and sold it as 200 lots. Among the first few purchasers of the land were Andrew Williams, a 25-year-old African-American shoeshiner; Epiphany Davis, a store clerk; and the African Methodist Episcopal Zion Church. From there, a thriving, autonomous Black community was born along what is now West 82nd to West 89th street.

When slavery ended in New York State in 1827, the population of Seneca Village flourished as the village's remote location provided a refuge from the densely populated downtown and the racial tensions that came with it. Evidence shows that residents had gardens and raised livestock and also used the Hudson River for fishing and a nearby spring called Tanner’s Spring as source for water.

By 1855, the village had a population of about 350 residents. Roughly two-thirds of those residents were free Black families, one-third Irish immigrants and a small number were of German descent. The village grew to be a middle-class Black community of five acres with streets, three churches, two schools, two cemeteries and 50 homes.

A map of Seneca Village.

NYC Municipal Archives

Once Central Park came, few traces of former community remained

After Olmsted and Vaux’s design for Central Park was chosen, the New York State legislature chose 750 acres of land, running from 59th to 106th street, to be the site of the new park. As the development of the park drew near, the media and politicians described the villages as “shantytowns” and targeted the residents as “squatters” and “vagabonds,” among other cruel descriptions.

The residents of Seneca Village persisted and fought to keep their community together; however, in 1857, the city used eminent domain to forcibly remove them. The village was eventually vacated and the city demolished Seneca Village, leaving little trace of the stories and people who had occupied it. Aside from a few recovered artifacts--beef bones, dishes, buttons, smoking pipes and the sole from a child’s shoe--historians have very little to tell them about what happened to the former residents.

In 2001, over 140 years after Seneca Village was destroyed, a historical marker was placed at its former location, and in 2019 the Central Park Conservancy installed a temporary outdoor exhibit of signage informed by decades of research, including the approximate locations of buildings that existed in Seneca Village.

Now, individuals can book tours with the Central Park Conservancy, focused on understanding the village’s importance to Black New Yorkers seeking refuge. However, more must be done to acknowledge Central Park’s Black history in a way that is permanent, free and accessible to every visitor--part of telling a more complete and inclusive story on and about our nation’s public lands.

If you would like to learn more about the untold stories of our public lands, check out The Wilderness Society’s Public Lands Curriculum, which reflects our broader effort to be more inclusive and equitable in our advocacy for the protection of public lands.